Back in May 2015, Donald Trump promised, “I’m not going to cut Medicare or Medicaid.”

That was then. Now that Trump is president-elect, enter Paul Ryan, Speaker of the House, who has long proposed privatizing Medicare, and now has not only Republican majorities in the Senate and House but a Republican president to presumably sign legislation passed by his party.

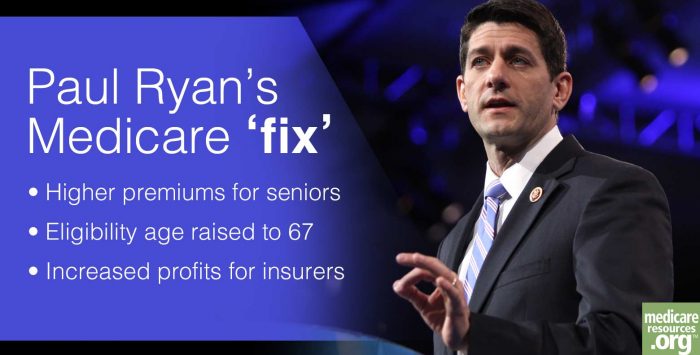

In a Fox News interview last week, Ryan announced his intention to make major changes to Medicare in legislation that would also “repeal and replace” Obamacare. “Because of Obamacare, Medicare is going broke,” Ryan declared. That’s the precise opposite of the truth. Changes to Medicare payment formulas included in the Affordable Care Act have have contributed to a slowdown in the growth of Medicare spending that has extended the estimated life of the Medicare Trust Fund by 11 years and reduced the Urban Institute’s ten-year estimate of Medicare spending by $2 trillion.

While Ryan did not specify the changes he has in mind for Medicare on Fox, he has long advocated transitioning the program from a “defined benefit” to a “defined contribution” system, in which seniors get a fixed sum they can use to choose a private plan from an array of options offered on an exchange, much like the ACA marketplaces established for younger Americans who need to buy their own insurance. Traditional Medicare would be one choice among many offered on the exchange, where private insurers would compete for enrollees’ business.

The choice we already have

Those with some experience of Medicare will note that something like this system already exists. At present, seniors can opt for traditional fee-for-service Medicare, which gives them access to all healthcare providers who accept Medicare, as some 97 percent do. Alternatively, they can choose from an array of private Medicare Advantage plans, which generally limit the choice of doctors and hospitals but also offer benefits beyond those provided by traditional Medicare – usually including, importantly, annual caps on the enrollee’s spending for hospital and physician care.1

At present, 69 percent of Medicare enrollees are in traditional Medicare and 31 percent in Medicare Advantage plans, which have rapidly increased their share in recent years. As Ryan’s most recent health plan notes, the Congressional Budget Office expects that share to rise to 44 percent by 2026. Medicare Advantage is in fact thriving, with insurers eagerly participating, despite cuts in payment rates put in place by the Affordable Care Act. Why, then, does Ryan want to restructure the market to accelerate the shift away from traditional Medicare?

How Medicare controls costs now

If Ryan does get a chance to create his “premium support” system, the likely effects will be twofold: more profit for the insurers and healthcare providers – and more costs shifted to seniors and away from the federal government. Because Ryan is studiously vague about key details, it’s hard to gauge how actual legislation would affect overall costs and seniors’ share. But it’s likely that by removing controls on how much Medicare Advantage plans pay doctors and hospitals, Ryan’s plan will raise overall costs – then shift them to seniors.

Medicare cost control is presently based on the fact that the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sets payment rates, working with a panel of doctors to determine how much labor is involved in each medical procedure, but ultimately determining the rates at which those estimated hours should be reimbursed. Those rates are much lower than those paid by private insurers in employer-sponsored plans.

At present, government payments to Medicare Advantage plans are tightly tied to traditional Medicare payment rates. For each county,2 Medicare sets a per-enrollee price target, or “benchmark” for MA plans to bid against. If their bid comes in below it, they are paid at the benchmark rate and must use the surplus either to offer additional services or to lower premiums. If they bid above the benchmark, they charge a premium for the difference over and above the standard premium for traditional Medicare Part B (physician services), currently $122 per month for most new enrollees.3

The ACA cut the rates that traditional Medicare pays to providers and incorporated those cuts in the formula by which Medicare Advantage benchmarks are calculated, as well as directly cutting the growth in payments to MA plans. The savings from closely controlled payment rates are effectively passed on to consumers, restraining growth in premiums and deductibles as well as federal spending on Medicare.

The cost control cord Ryan would cut

In the plan he released this spring, Ryan castigates these measures as government control of healthcare:

Despite MA’s popularity and bipartisan appeal, Obamacare cut the program by $150 billion when it was signed into law in 2010. The law’s cuts have reduced MA’s ability to meet the needs of patients and those effects are compounding over time.

Ryan cites no data to back that last assertion up, because he can’t. “Since the ACA passed in 2010, the share of all beneficiaries enrolled in a private plan has increased from 24 percent to 31 percent,” notes Tricia Neuman, Director of the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicare Policy. “There is precious little evidence to say whether the cuts have affected the ability of Medicare Advantage plans to meet the needs of patients, particularly those with serious and complex health problems.”

Beginning in 2024, Ryan would replace the current system, in which the government creates the benchmark based on traditional Medicare rates, with one in which the benchmark is the average of all received bids.4 That cuts the direct tie to traditional Medicare rates.

What remains unclear, because Ryan keeps his plans vague, is whether he would reduce the share of each enrollee’s premium paid by the government as premiums rise over time. At present, Medicare pays three quarters of the premium for Medicare Part B for 95 percent of enrollees. (High-income seniors pay higher percentages.) The value that enrollees get for their three-quarters-subsidized premium has also remained stable: traditional Medicare pays about 84 percent of the average enrollee’s yearly costs. Medicare Advantage plans cover a comparable percentage of costs, and their premiums are benchmarked to those of traditional Medicare, though a given plan may charge more or less.

In prior versions of his privatization plan, for example in his budget for 2013, Ryan set a cap on how much Medicare costs could grow in a given year (GDP growth plus 0.5%). If cost increases exceeded the cap, the plan strongly implied, those excess costs would be borne by enrollees. The cap was meant to “serve as a fallback to assure federal government budgetary savings,” which indicates that if it were exceeded, consumers would bear the cost. More recent versions, including this year’s, do not reference a cap.

When empowerment means ‘you pay’

To keep costs from growing too fast, Ryan extols the effects of competition and sings the praises of “empowering patients” by giving them more choice. Here’s how he put it in his 2013 plan:

When it comes to controlling health care costs…the question is: Who gets the power? One centralized federal government, or 50 million empowered seniors holding providers accountable in a true marketplace?

Insurers are competing enthusiastically in the current Medicare Advantage market, however, despite – or even because of – the guardrails within which insurers operate. To remove those rails, which are bolted to the government’s prerogative to set baseline prices, is to risk escalating payment rates to providers, which will very likely be passed on to patients. “Empowering” seniors will very likely translate to making them pay a larger share of their Medicare premium, thereby “empowering” them to push insurers to keep premiums low. But since insurers will likely be paying more to healthcare providers than under the current system, the beneficial effects of such a push are, shall we say, theoretical.

Ryan also proposes to gradually raise the Medicare eligibility age to 67, a change that will fall particularly hard on lower income people, who in today’s America have sharply lower life expectancies than the affluent. The change would cause especial hardship if Republicans repeal the Affordable Care Act and fail to put in place a replacement that renders coverage affordable to the near-elderly. Since Republicans’ sketchy ACA replacement proposals also call for increasing the multiple that insurers can charge to older enrollees compared to younger ones, their plans are a particular threat to the “young elderly.”

Bottom line: In the name of consumer choice and consumer control, legislation shaped by Ryan would likely lift the lid on the payments insurers make to healthcare providers – and then, as costs rise, shift an ever-rising share of them to seniors.

Tags: Medicare Advantage, repeal and replace, Traditional Medicare, Donald Trump, fee-for-service, Paul Ryan, premium support